At first glance the notion of a national economy would seem to be self-evident. After all, the lion’s share of economic data comes in the form of “national accounts,” which treat the nation as a self-contained economic entity, like a business. And the talk, when it comes to the economy, is always of how the nation is doing, or how other nations or countries are doing. Likewise, history revolves around the nations and their economic progress, as with the US and its “manifest destiny.”

But the idea of a national economy does not extend to the level of theoretical category. Economic theory does not take it into consideration. It comes into play because of political, not economic, considerations. The fact of the matter is, because politics is concentrated at the national level, so also is fiscal and monetary policy. And this factual state of affairs determines the subject matter. It is at the national level that both fiscal and monetary policy takes place; it is the level at which results from these policies are expected.

Economic theory, however, is not discussed in terms of the nation but in terms of abstractions: the “market,” “business,” “consumers,” etc. This is, or at least it used to be, referred to as “microeconomics.” Then we have “macroeconomics,” which is essentially the economic role of the state with its aforementioned fiscal and monetary policies; in this way we smuggle the nation in through the back door, as it were.

But the nation never functions as a subject of economic theory in its own right. Economic practice, of course, cannot avoid it – the sovereign democratic state is the way things are, it delimits the subject matter at the “macro” level.

The unexamined presupposition in all of this is, what is the locus of the economy? It is actually a question of the utmost importance, because only in this way can we come to grips with crucially important notions – and realities that, like it or not, we have to deal with – like the “global” economy.

One person who, thankfully, did not leave this presupposition unexamined is Jane Jacobs. In her book Cities and the Wealth of Nations,[1] she puts the notion of a national economy, which she takes to be the reigning doctrine, squarely in the cross-hairs. In her view, such an economy is an artificial imposition: the real economy is city-oriented. Cities, not nations, form the watersheds of an economy. Which is to say, cities are the focus of integrated, mixed economies, involving all major sectors from agriculture to industry to finance. Within the city and its supply regions, a stable and integral economy is maintained.[2]

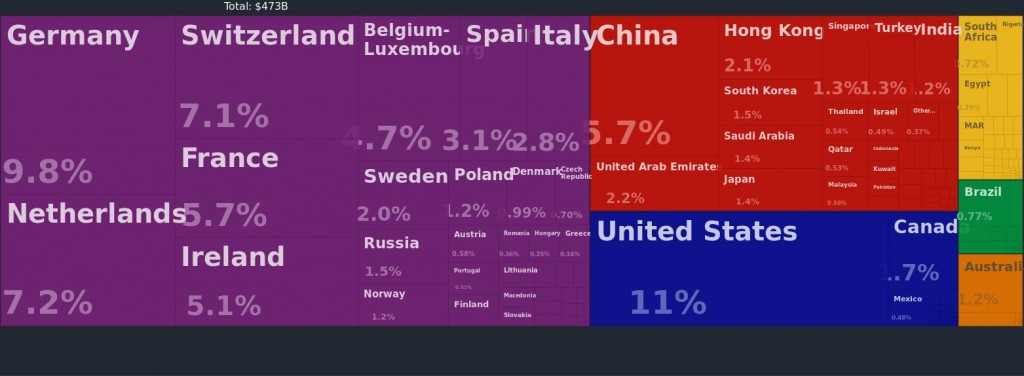

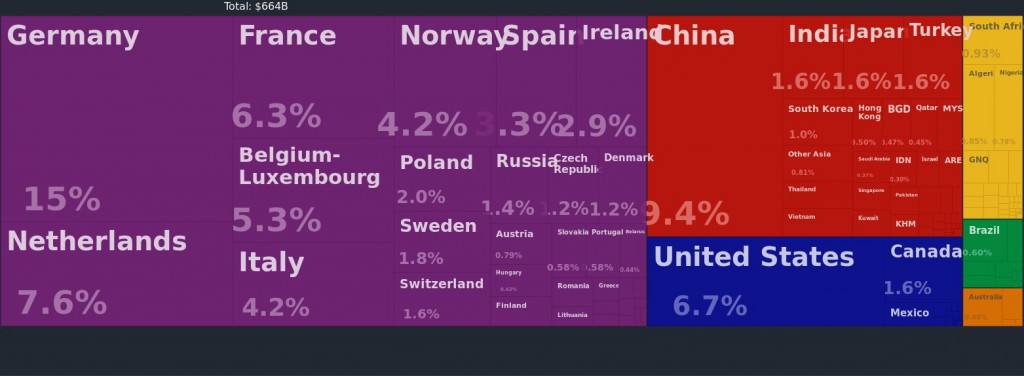

Therefore exporting and importing takes place between cities, not nations. By extension, cities perform the vital economic function of import-replacing: the replacement of imported goods with goods of their own making. In Jacobs’ model, it is this import-replacing function that is the basic motor of economic growth.[3]

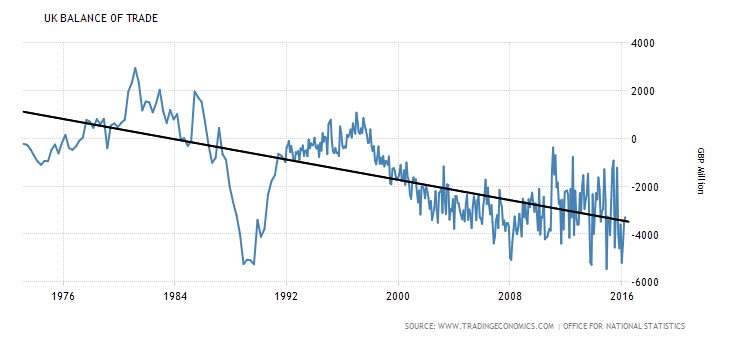

Jacobs adds to this import/export functionality the logical corollary: currencies. Currencies function as feedback mechanisms: they provide economies with information with respect to their productivity vis-a-vis other economies. A rise in an economy’s currency indicates that it is more productive than other economies the currencies of which are falling in relative terms, while a fall indicates the reverse condition.

So then Jacobs draws the obvious conclusion. Since cities are the basic units of import and export, currencies, in order to best perform their function, should be geared to the city economy itself; their rise and fall would thus trigger the appropriate response in the city economy, because this currency fluctuation acts as both tariff barrier and export subsidy (a falling currency acts as an export subsidy, a rising currency as a tariff barrier). Cities should maintain their own currencies.[4]

This also indicates a problem with this entity known as the national economy. A larger political unit such as a nation-state, when it imposes a common currency on a multiplicity of cities, short-circuits this feedback function of currencies. It favors the economies of some cities at the expense of others. Since cities not only import and export to foreign nations but also to sister cities in the same nation,[5] the automatic feedback information provided by the currency does nothing to allow cities within the range of the currency to adjust their economies to each other. They receive none of the feedback information that a city-based currency would provide them. Therefore, the cities whose economic position is favored by the national currency continue to grow, while the others stagnate.[6]

Clearly Jacobs is no friend of the nation-state. “Virtually all national governments, it seems fair to say, and most citizens would sooner decline and decay unified, true to the sacrifices by which their unity was won, than prosper and develop in division.”[7] And she takes classical economics, especially as exemplified in Adam Smith’s tellingly titled Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, to task for this. Smith “accepted without comment the mercantilist tautology that nations are the salient entities for understanding the structure of economic life. As far as one can tell from his writings, he gave that point no thought but took it so much for granted that he used it as his point of departure.”[8] Smith’s unthinking assumption of this assumption was subsequently passed from generation to generation without any further thought on the matter. “Ever since, that same notion has continued to be taken for granted. How strange; surely no other body of scholars or scientists in the modern world has remained as credulous as economists, for so long a time, about the merit of their subject matter’s most formative and venerable assumption.”[9]

So Jacobs agrees with us that the locus of the economy is an unexamined proposition. Nevertheless, her thesis that the nation was the focal point of classical economic theory is debatable. In fact, it is contradicted by an early proponent of “The National System of Political Economy,” Friedrich List.[10] List certainly does not figure as an unthinking follower of Adam Smith. His description of Smith’s school is telling: he calls it “the Cosmopolitical System.” By which he means that, pace Jacobs, it is the antithesis of a “national system” of economics.

In line with the influential vision of “Perpetual Peace” put forward in the late 18th century by the celebrated Abbé St. Pierre, this “cosmopolitical system” of economics presupposes harmony and peace between the nations. In such a situation, nations per se have no interests; the human race is joined together as one; and for this reason, “for the most part the measures of governments for the promotion of public prosperity are useless; and that to raise a State from the lowest degree of barbarism to the highest state of opulence, three things only are necessary, moderate taxation, a good administration of justice, and peace.”[11] Free trade is then the norm, and indeed, can only truly be implemented under the auspices of such a universal peace. But, argues List, this is to confuse a hypothetical goal toward which the nations should work, with a standing condition already attained.

The [classical] School has admitted as realized[,] a state of things to come. It presupposes the existence of universal association and perpetual peace, and from it infers the great benefits of free trade. It confounds thus the effect and the cause. A perpetual peace exists among provinces and states already associated; it is from that association that their commercial union is derived : they owe to perpetual peace in the place they occupy, the benefits which it has procured them. History proves that political union always precedes commercial union. It does not furnish an instance where the latter has had the precedence. In the actual state of the world, free trade would bring forth, instead of a community of nations, the universal subjection of nations to the supremacy of the greater powers in manufactures, commerce, and navigation. [12]

While Smith and the other proponents of the classical school did recognize the existence of nations and national interests, List correctly assesses the basic orientation of the system. Much of this was inchoate; Lists’s strictures served to stir up debate, generate criticism, and give rise to critical schools of economic theory, such as the so-called Historical School.

This is evident not only in the advocacy of free trade generally as panacea for all economic ills, but also, importantly, in the advocacy of free trade in the area of currency. As we explored in this earlier post, leaving currency to the free market is a key element in a cosmopolitan system that deemphasizes nations as economic actors and subjugates sovereignty, in order to establish a “center-periphery” system of exploitation. And Adam Smith’s classical system established commodity money as a cornerstone of its economic order. As such, in its essentials List’s construct holds true.

List is correct to point out that mercantilism, the target of the classical school’s vituperation, took the nation to be the focus of economics. The system of commodity money, established to overcome mercantilism, is thus a product of the cosmopolitan system. Indeed, the latter found its justification in the fact that it overcame mercantilism, with its supposed framework of conflict of interests and the struggle between nations.

The system of commodity money came to be embodied in the gold standard. As I have argued elsewhere (Follow the Money, ch. 14: “The Great Transformation”), that system ended up in the shipwreck of two world wars and a great depression. As such, it is forever a thing of the past.

Since then, we have had national currencies; and since 1971, ostensibly free-floating national currencies. Jacobs’ polemic against the current system of national currencies has this to say for it, that it understands the role of currencies as feedback mechanisms. Furthermore, the understanding of economies as things that are city-oriented and city-generated. Where Jacobs goes astray is in her exclusive focus on currencies as the only way imbalances are rectified.

As I outline in the accompanying course, economic regions within national boundaries, which thus share the same currency, adapt to each other and resolve imbalances between each other by changes in wages and prices. These changes trigger flows between the economic regions, which are called factor flows: flows of mobile factors of production. Two such factors are labor and capital. They flow back and forth between economic regions, depending on such things as wage levels, price levels, and interest rates.

In the cosmopolitan system, these flows take place not only within countries but between countries. The world is then viewed as a unified, universal jurisdiction of provinces, with the free flow of mobile factors of production settling up regional imbalances.

The problem with this system is, of course, that it does not take nations into account as inescapable realities with inescapable, differentiated, often conflicting characteristics. Nations have different cultures, languages, religions, mores, values, levels of material development, and certainly different approaches to and attitudes towards getting and spending. This leads to evident differentials in things like rates of economic growth.

There is more. Nations have an unsettling penchant: inner drive to establish sovereignty. This was one of the great insights of the German Calvinist statesman and political philosopher Johannes Althusius (1563-1638). At the time, the doctrine of sovereignty was for the first time being fully developed in its modern form as the power that cannot be gainsaid, the power that stands above all other human institutions and authorities and “speaks the law” to them in a final manner. The Frenchman Jean Bodin (1530-1596), coincidentally one of the forerunners of the theory of commodity money, was also the developer of this new theory of sovereignty, which he located squarely in the ruler, whether king or national assembly of whatever sort.

Althusius accepted Bodin’s doctrine of sovereignty but turned it on its head, as it were. It was not the ruler, but the nation as a whole which was the bearer and locus of sovereignty. The ruler was simply the administrator thereof, who exercised its power in the name of and in trust to the true sovereign, the people or nation.

I have attributed the rights of sovereignty, as they are called, not to the supreme magistrate, but to the commonwealth or universal association. Many jurists and political scientists assign them as proper only to the prince and supreme magistrate to the extent that if these rights are granted and communicated to the people or commonwealth, they thereby perish and are no more. A few others and I hold to the contrary, namely, that they are proper to the symbiotic body of the universal association to such an extent that they give it spirit, soul, and heart. And this body, as I have said, perishes if they are taken away from it. I recognize the prince as the administrator, overseer, and governor of these rights of sovereignty. But the owner and usufructuary of sovereignty is none other than the total people associated in one symbiotic body from many smaller associations. These rights of sovereignty are so proper to this association, in my judgment, that even if it wishes to renounce them, to transfer them to another, and to alienate them, it would by no means be able to do so, any more than a man is able to give the life he enjoys to another. For these rights of sovereignty constitute and conserve the universal association.[13]

This key consideration is something that Jacobs and economists in general overlook. Sovereignty is a legal and political doctrine that fixes economic reality in a determinate and conclusive manner. It transcends economics while also acting as a basic datum that real-world economics must take into consideration. And it is nations that exercise sovereignty. As such, it is nations that establish and maintain a common law, the determiner of economic reality: hence, common-law economics. Currency, for one thing, is a function of this common law. No nations, no sovereignty; and no sovereignty, no common law. As this piece is already long enough, I will spare the reader any further elucidations. But this on-site article can serve to fill the gap.

[1] Jane Jacobs, Cities and the Wealth of Nations: Principles of Economic Life (New York: Random House, 1984).

[2] Ibid., ch. 2.

[3] “Whenever a city replaces imports with its own production, other settlements, mostly other cities, lose sales accordingly. However, these other settlements – either the same ones which have lost export sales or different ones – gain an equivalent value of new export work. This is because an import-replacing city does not, upon replacing former imports, import less than it otherwise would, but shifts to other purchases in lieu of what it no longer needs from outside. Economic life as a whole has expanded to the extent that the import-replacing city has everything it formerly had, plus its complement of new and different imports. Indeed, as far as I can see, city import-replacing is in this way at the root of all economic expansion.” Ibid., p. 42.

[4] Ibid., ch. 11.

[5] Ibid., p. 43.

[6] Ibid., ch. 11.

[7] ch. 13; the quotes are from pp. 212, 215-16.

[8] Ibid., p. 30.

[9] Ibid., p. 31.

[10] As elaborated in his book The National System of Political Economy, first published in German in 1841. The English translation was first published in 1856.

[11] National System of Political Economy (1856 ed.), p. 191.

[12] Ibid., p. 200.

[13] Frederick S. Carney (trans. and ed.), The Politics of Johannes Althusius (London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1965), p. 10. Emphasis added.